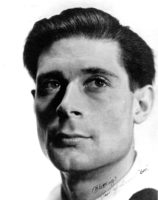

Alan Chadwick (27 July, 1909 – 25 May, 1980) was born in England into an aristocratic family at the seaside resort of Saint Leonard’s-on-Sea. He was the second child of parents both on their second marriages, and had an older brother, Seddon. His mother, Elizabeth Alcock Chadwick, was a refined woman with an artistic nature and involved at the time with the Theosophical Society, and then later became associated with Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society.

Alan Chadwick (27 July, 1909 – 25 May, 1980) was born in England into an aristocratic family at the seaside resort of Saint Leonard’s-on-Sea. He was the second child of parents both on their second marriages, and had an older brother, Seddon. His mother, Elizabeth Alcock Chadwick, was a refined woman with an artistic nature and involved at the time with the Theosophical Society, and then later became associated with Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society.

By all accounts including his own, Alan was an extremely shy, sensitive child, who was introduced to the arts at an early age by his mother, especially gardening and the theater. He loved Nature and gardens. At five years old, Alan said he was taken to see Maurice Maeterlinck’s play, The Bluebird, and later in life declared:

“…it carried me right out of this world, for two and a half hours, I was in another world, my ears began to sing and suddenly it all ended; then the lights came back on, it all closed down and I was back in myself again. But it had happened, I had entered the theater!”

As a youth and young man, Alan was tutored by more than a few people in his mother’s social circles, including Rudolf Steiner. Late in life, Alan spoke of being a “child of Steiner; he was the one tutor who had the deepest lasting influence upon me.” He then studied at some of the finest horticultural schools in England and on the Continent, before renouncing his inheritance and commencing theater training with Madam Elsie Fogerty at the Central School for Speech and Drama in the Royal Albert Hall, London. After his studies, he pursued a career in the theater.

Chadwick said that his favorite play, other than Shakespeare’s plays, was John Drinkwater’s Abraham Lincoln, because of Lincoln’s suffering, melancholy, wisdom, humor and humility. He played Lincoln in much the same manner as Hal Holbrook played Mark Twain.

Alan was a conscientious objector at the outbreak of World War II, but due to family and peer pressure, he volunteered for the British Navy in 1940 and served on a minesweeper. He described in detail two tragic events to journalist Bernard Taper, wherein his back was injured during the war. Due to these experiences, he suffered pain for the rest of his life and could no longer play the violin.

After briefly returning to England and working in the theater, he then emigrated to South Africa, to get away from England and war memories. While there, he worked in the newly formed National Theater Organization and created a large, beautiful garden for the Admiralty House Estate in Simon’s Town. Here Alan also met Freya von Moltke, who narrowly escaped Germany at the end of the war with her two sons. She remained Chadwick’s closest friend, muse and confidant for the rest of his life.

It is difficult to capture the essence of his life as there are so many sides to Alan Chadwick. He was a master gardener, painter, actor, singer, an incredible cook, lover of cigars, fine coffees and wines, a raging prophet, a childlike imp full of playfulness and joy, temperamental, mercurial, restless, a superb storyteller and a giver of all he had to give. He was intolerant of laziness and dullness, a lover of classical music, painting, poetry, fables, myths and fairy stories. Alan wanted everyone to wake up and live, to become their true innermost selves.

As to Alan’s well known artistic volatile temper, aside from wartime PTSD, one is reminded of Beethoven who was known to throw breakfast trays at maidservants, screaming at them to “Get out! You are interrupting my work!” The result of the art is all that matters to these great artists; they suffer and the people around them sometimes have to endure the maelstrom. However, it is the world that receives the gifts; the Fifth Piano Concerto; the Ninth Symphony. Or a vision of what gardens can be, obedient to the laws of Nature. As Kahlil Gibran wrote, “out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls. The most massive characters are seared with scars.”

Everyone who knew him felt there was no one else like him. Each person had their own unique experience of Alan Chadwick, one experience not more important, better or worse than another, just different. As one apprentice put it, “Everyone has their own personal view of Alan’s inner movie.” As to Alan’s treatment of women, so misunderstood by many, he stated that if humanity is going to change its approach to Nature, it will come through women and the divine feminine in us all. Alan Chadwick was and remains one of a kind, one of any kind. His work, vision and legacy have influenced thousands of lives worldwide.

For Alan, it was all about art and high culture. He needs be spoken of in the same breath as Rachel Carson, Gertrude Jekyll, Luther Burbank, Rosemary Verey, Vita Sackville-West, Margaret Fuller, John Muir, William Morris, William Robinson, Russell Page, Jens Jensen, John Ruskin, Thoreau, Emerson, L. H. Bailey, Wendell Berry, Robert Rodale, Masanobu Fukuoka, Wes Jackson, Sir Albert Howard, Dr. Rudolf Steiner, Lord Walter James Northbourne, Lady Eve Balfour and others.

Alan Chadwick never wrote a book, and unfortunately gardens do not survive like architecture, theatrical plays, piano concertos, paintings or poetry, because it is what Alan did that is important, maybe even more so than what he said. However, what he said points to very deep principles and truths. Thankfully, his lectures to apprentices, public talks and interviews have survived, and they serve to inspire and uplift us all.

For a more complete biographical sketch, see Robert Howard’s “What Makes Crops Rejoice”.